Playing The Mountain Witch makes your table better at playing roleplaying games.

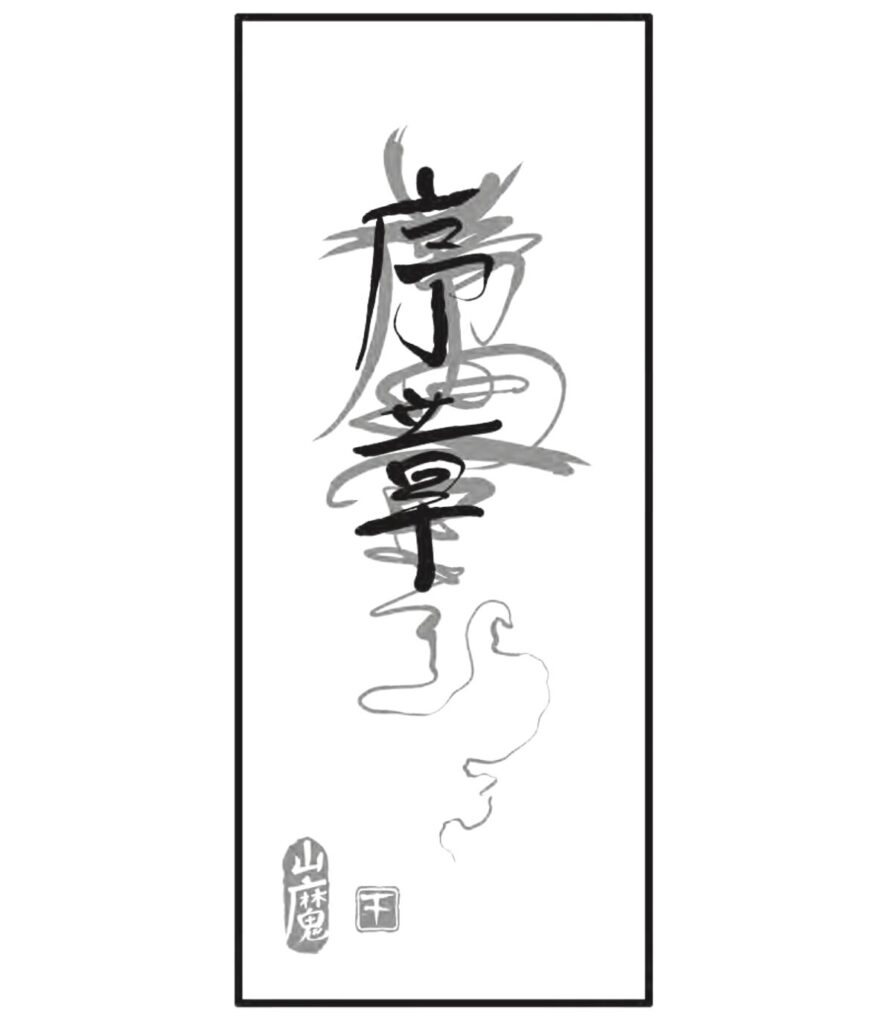

The Mountain Witch was released in 2005, and I was active in online RPG circles at the time, where it would’ve been discussed, and could be that I’ve run it since around then. I believe we first played the game jam version of the game, and the complete PDF release might’ve been the first digital tabletop roleplaying game I ever bought.

I like to run it with a different group every time. I’ve often run the game for players new to my table. We feel it gives a good idea of how a player fits with us, and it gives the player a good idea of the kind of games we play – heavy on drama and player character on player character action, be that antagonistic, romantic, or complicated.

Improvisation exercise

Playing The Mountain Witch is different from most roleplaying games. Each player has a dark fate, hidden from the other players. It is each player’s goal to bring their dark fate into play and resolve it, as dramatically and satisfyingly as they can. There is very little other content in the game.

On the surface, the ronin are ascending a mountain to kill the witch. The witch is a McGuffin – I make it clear to players that the witch might not even exist, and if it does, it is only in the service of the players’ dark fates. Often, the players don’t even reach the witch’s castle. The players’ goal is not to find the witch: their goal is to meet their dark fate.

What does “advancing your dark fate” look like? First you need to introduce the elements of your fate to the table, typically by way of somewhat cryptic clues, then you need to engage the fate by bringing elements of it more explicitly into play, and finally you need to resolve it, through some sort of direct conflict.

When your dark fate involves other characters – and it always does – it is recommended that you don’t bring in external characters, but rather find a way to involve the other player characters. Most players have a strong threshold for doing this sort of thing, as you’re broaching the agency of other players at the table, and in this game we give you explicit permission, even a requirement, to do so.

The gamemaster does not advance the story. They simply move the player characters on the path, adding mechanical resistance (physical challenges, often combat) in each of the three acts until every player has advanced their dark fate.

If you don’t advance your dark fate, the whole player group pays the price, so there’s a strong incentive – and license! – to do so. If you don’t, the gamemaster will spring another challenge on everyone, with the odds quickly stacking against you.

You’re not supposed to wait for your time in the spotlight, but rather create it.

Pacing exercise

You only have a very limited number of scenes to bring your dark fate into play. The game is split into three acts, and each act will have a couple of scenes in it.

There isn’t enough room in this structure to give each player a scene of their own in each act, but each player needs to advance their dark fate in each act. I make every player aware of this in the beginning of the game.

This means that the players are constantly looking for a way and an opportunity to bring their dark fate into play. This creates very dynamic play that is looking for ways to expand even when nothing much seems to be happening in the fiction.

While actively looking to advance your personal story, you’re also forced to consider the game’s overall pacing – you need to advance your story in each of the three acts. So you can’t go all out from the onset. You have to build a dramatic arc.

The power of the ritual

The story always starts at the foot of the mountain (I always start it at an inn or an onsen), the ronin are put on the path, and they start working on their dark fates to resolve them as dramatically as possible.

This is a powerful ritual, and to players who’ve played the game before, it instantly puts them in the right context. You can skip a lot of boundary and context setting, and start weaving the story together.

How this is useful in other games

What you get out of playing The Mountain Witch is a couple of things. First, it proposes the idea that the roleplaying game is about the player characters, and whatever is going on in their personal stories. I subscribe to this line of thinking strongly, even if lately I’ve been running pre-written scenarios, which are more like a haunted house or a fairground ride in nature – the characters don’t actually matter all that much, it’s about going through a pre-designed experience together, as players.

Second, players learn how to work with their personal stories in any game. In other games you might not have a dark fate that will likely leave you dead in the snow in a couple of real world hours, but you probably do and should have unresolved conflicts in your character’s background.

What I’m saying is that you should resolve those. That creates great play at the table – as long as you know how to present, pace, and turn those tales towards the table, as opposed to handling these sorts of personal matters between the scenes.

Third, The Mountain Witch has player versus player built into it, complete with a fun bluffing/betting dueling mechanic, and a central trust mechanic, which is the only way for players to increase their odds in challenges during the game. Player on player conflict isn’t required, but most Mountain Witch games will feature some. Most games shy away from encouraging PvP, often for a good reason, but Mountain Witch teaches players how to work with PvP, using it as an ingredient in building satisfying character arcs. The trust mechanic makes tension between the characters tangible, and teaches players to think about their character’s relationships with the other player characters as a dynamic thing. This is useful in any game.

What to do next – Trophy

The Mountain Witch is somewhat dated in 2024, and could use a fresh edition. That doesn’t look like happening after the author disappeared from the internet following a successful crowdfunding campaign for a second edition. I’ve read Trophy Dark/Gold since, and feel that they could be the new Mountain Witch for my table. I’m planning to test those the next time I feel like running The Mountain Witch.

Leave a Reply