Darrington Press is the publishing arm of Critical Role Productions. They’ve been at it since 2020 and released a variety of games and products for games. Daggerheart (2025) is what the fanbase has been waiting for: their take on Dungeons & Dragons.

If you’re unfamiliar with modern, fifth edition D&D, and pick up some of its books and the Daggerheart book, you’d be forgiven to think it’s all part of the same. On the surface, this is very familiar, very well trodden territory of high fantasy cliches. Daggerheart adds a couple of races that are probably too quirky for Wizards of the Coast (the monkeys, the frogs, and the mushroom people), but looking at it? They’re the same.

You have your adventuring party, with clear class based roles for all players. You have tiers of play. You have loot tables. All characters get a whole suite – or in this case, a deck – of special powers. The game is built around combat. If you visualize what that combat looks like, it’s going to be very colorful, with special effects flying from each attack.

What made me pay attention is a couple of things. First, a reviewer I can no longer locate (sorry!) said that Daggerheart is for people who don’t like D&D combat. I find D&D combat too slow these days and would rather spend my time on something else, so that sounded interesting! Another reviewer I can’t locate said Daggerheart is D&D with feelings. That sounds great!

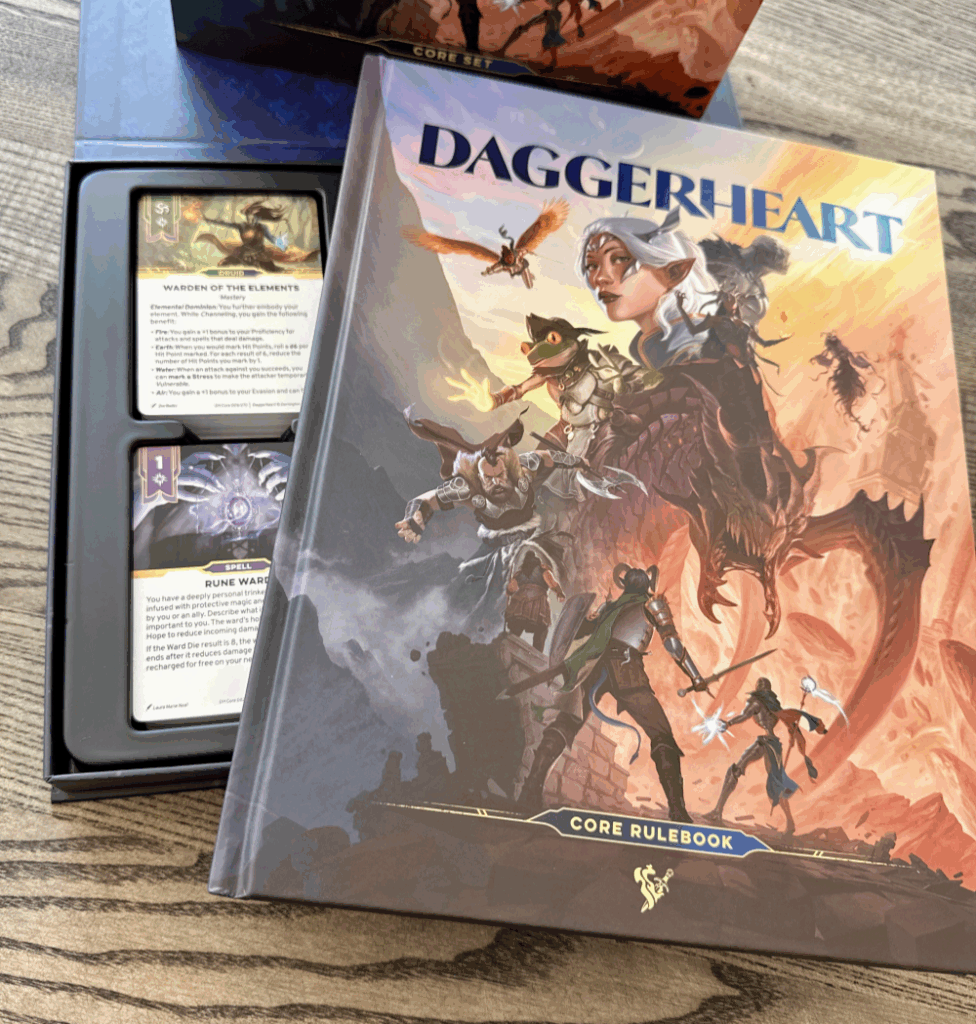

Second, this 366 page book includes everything: the rules, character creation with the hundreds of powers, extensive GM advice, bestiary, and campaign frameworks. All this, plus all the cards you need for character creation and play, for the price of a single D&D manual.

Finally, Darrington Press calls this a narrative-driven game. While bowing deep to its D&D roots, with all the baggage that entails, this is a bold claim, and something I wanted to see for myself.

Things I love

The book is very well written, and especially concise. While I also like the 2024 editions of D&D manuals for how well they’re written and how accessible they are, they still use up a lot more page count to get these same things across.

Look at the classes: each class is a single spaciously laid out spread, with big hero art, and including two sub classes for each! Yes, some of them then get extra options over the following pages (druid’s beastform options take two more spreads), but the way this respects my time and feels like the game wants to be taken to the table is special.

The classes all read distinct. There are nine, most of them direct lifts from D&D : sorcerer, druid, ranger, warrior, guardian, seraph (celestial paladin, or cleric with a big sword and optionally wings), wizard, bard, and rogue. The only big change from D&D is really that the cleric has been changed into a frontline fighter. This is very welcome. Compared to first level characters in D&D 5th edition, the heroes are very capable right from the first level. This reminds me of D&D 4th edition – there are quite a few 4th edition callbacks, which is great, as that is in many ways my favorite edition, even if it was short lived and you couldn’t really play it without a robust digital tool kit.

Each class is a combination of two domains. This means that they all share domains with other classes. This is an interesting approach, especially since the card pool from which the players select their domain powers from is shared: each card can only be taken once. The domains themselves are a little artificial and don’t make immediate sense as a whole. There are quite a few: arcana, blade, bone, codex, grace, midnight, sage, splendor, and valor.

As a design slip-up, the domains are only referenced by their symbols in many places. Because there are so many (nine), this feels like a mistake. You don’t really need to identify them outside of character creation and level-up, though, and each player only needs the two domains, so it’s not too much of a bother.

The math reads pretty clean and something that has been tested. I love that the attributes only get their very D&D like bonuses (+2…-1), and we skip the old school 3-18 number assignment altogether.

The stats are very familiar, only slightly tweaked from the source material: agility (athletics type dexterity), strength, finesse (nimble fingers type dexterity), instinct (wisdom), presence (charisma), knowledge (intelligence). I’m not sure about the two DEX type stats – even if I forego 35 years of D&D conditioning, the two feel too similar, and I get the feeling they wanted a difference there just to be different from D&D. I’ll give that athletics being under strength always felt weird, and that constitution was a stat only needed for hit points, which in Daggerheart are tied to class instead of stats.

Character creation is really streamlined. You pick your class (9 options), ancestry (18 very colorful options), and community (9 options), each represented by a card you pick. Character traits (attributes) are assigned from a standard array of +2, +1, +1, 0, 0, -1, and each class comes with a recommended set. There are not a whole lot of derived stats, either: evasion (armor class), hit points (set by class, 5-7), and stress (6).

Hope is a meta currency that powers most of your special abilities (cards). You start with two, and can hold a maximum of six. Make a couple of choices from your starting kit, and mechanically, you’re done with character creation. You can’t even go shopping for more gear!

The game comes with quite a few colorful, well designed, sturdy cards, containing all the powers you can get in character creation or at level up. In-game, you can have a maximum of five “active” (in addition to your three “base” cards). I love this! It’s an arbitrary solution to the D&D power management paralysis, where a player’s brain capacity is absorbed by pages of powers. Beyond the five, the rest are in your “vault”. You can swap powers when you sleep, or by paying a cost in stress.

A lovely detail about the cards is that even if you had multiple sets at the table, you’re encouraged to only give out each card once. This helps keep the player characters distinct, and lets them shine on their own terms. Great stuff. Of course, with all powers being cards, you also get to skip writing down each power on your sheet.

I imagine that if the game is successful, there will be expansion sets of cards for new classes and domains. It feels like a tangible way to go beyond the core experience, but of course raises the bar for homebrewing your own stuff.

There are lots of examples, and they’re very well written. The long example of play at the end of the player facing rules is exceptional. It includes plenty of moments where the GM has to make a judgment call, and is completed with an after action discussion where the would be-GM reading the book is asked questions about various moments in the example – would they have decided otherwise, and why? It’s perhaps the best example of a typical game’s GM decision making in practice that I’ve seen in a book.

While I am heavy on the game lacking clear rules for many situations, the Fear point economy is well thought out. Every player roll brings the chance of the GM getting a Fear point, as well as getting to make a move. This brings a welcome, constant tension to play. Every time the PCs rest, triggering a downtime scene, the GM gets Fear points, and gets to advance one long-term clock, bringing a major, likely dangerous event closer. There is a Fear point cap of twelve, encouraging the GM to spend them in the next big scene. Because the GM’s Fear points should be tracked publicly, this gives the players the opportunity to dread the rising point count, and wonder about the challenges ahead of them, as the GM will want to spend the accumulated threat.

A detail that I love is that there are no magic rules. D&D magic is something I detest, and this just puts all character special abilities on the same line. Need to see how it plays, but I love this in principle.

Things I don’t like

The damage rolls only being used to see whether the damage is enough to cause minor, major, or severe wounds, resulting in 1, 2, or 3 hit points being lost feels like an unnecessary conversion step. Thinking about it, you do the same in D&D, too, where the largest hit point pools force you to estimate the impact of your attacks to understand if you had an impact or not. Here that impact is more clear, but the conversion step is mandatory. It does allow for armor to work in a fun way, dropping the severity of the hit, from 3 to 2 to 1 to no damage.

I get the feeling the damage rolls are here only to be able to bring the whole standard array of polyhedral dice to the table, and D&D accustomed players liking to roll damage. Without seeing how this feels at the table, hard to tell if it works in practice, but it reads clumsy.

Saving throws (called reaction rolls here) are a strange holdover from D&D lineage. I’ve always disliked them, maturing into actual hate over recent years, and this implementation is no different. At least they don’t take space from the character sheet. Why do you have these things? Their function is to perhaps undo something that already happened in the fiction.

There are ranges in combat, but the book goes out of its way to explain how non-specific they are. I don’t quite know what purpose this serves, especially as there are ultimately also squares given as an option, if you want to recreate D&D combat. It feels like it would’ve preferred no ranges, but didn’t dare to go quite that far.

Narrative-driven heroic fantasy

So far the game is a very streamlined D&D lookalike – much more accessible, dare I say it more fun, but ultimately? It’s D&D fantasy. What about this is then “narrative-driven”?

It starts with the basic mechanic. You roll two twelve-sided dice, different colors, one being “hope” and the other being “fear”. Whichever is highest in a given roll determines the flavor of the outcome, driving the fiction into a definite direction. These outcomes also feed either the player’s Hope pool, or the GM’s Fear pool. Interestingly, and I feel in a good way highlighting how the story is about the player characters, when the GM rolls, they roll with a D20 instead – very unpredictable, and no Hope or Fear are generated.

Unlike D&D, the GM is encouraged to avoid rolling if the roll would not change the fiction. A roll that doesn’t matter shouldn’t happen. Every roll should come with exciting outcomes, including “yes, and” for success with Hope, “yes, but” for success with Fear, “no, but” for failure with Hope, and “no, and” for failure with Fear. This does create extra pressure on the GM to improvise varying outcomes, but they are encouraged to include the other players in coming up with these less binary results.

Looking at the classes, they all come with a selection of evocative questions to help shape your own background, and crucially, your relationship with the other player characters. I would’ve liked these lists of questions to be longer – you now get three of each type of question – but it’s more than what D&D offers, even with the latest edition’s new focus on character backgrounds. This feels especially problematic considering how the entire game will later be built around the answers to these questions. Also, surprisingly, these bonds serve no mechanical purpose in the game, which I feel is a miss. It’s easy to see how they could play into the Hope/Fear dynamic.

There is no skill system as such. Instead, all characters start with two “experiences”. Those can be anything, but they’re assumed to describe their profession, personal style, or signature personality traits, like “stubborn”. When they would help you in a situation, you can spend a hope point and get a +2 to your roll. Yes, exactly like Fate. You’re encouraged to come up with one applicable in combat, and one outside of combat.

I think new players might struggle with this experience approach. I remember how difficult Fate’s Aspects were initially for me, and it took a bit of handholding and table experience to click. Here you only get one page of advice. You’re encouraged to tweak and change the experiences if they don’t see use at the table, which is great permissive and accessible design.

Something the game does very well is a constant emphasis on how the mechanics are not tied to a specific in-fiction manifestation, and that players are expected to make all of it their own. Your armor, weapons, and attacks can look like anything. You can adventure and fight in a wheelchair. You can change bug magic to plant magic, if you’re averse to bugs, without touching a thing in the rules. This feels decidedly modern, and makes D&D look antiquated in comparison.

The GM advice on how to build a game world and story revolving around the player characters is great stuff! I wish it went into more detail, but following these guidelines on multiple story arcs and personal meaning will likely give you a very satisfying, personal story for all players.

How do you fight?

There is no combat system. Attack rolls have some slightly more detailed rules about them, primarily being followed up by a damage roll. There is no list of actions you can take in combat, literally there are no combat actions. I find this very refreshing, both because it makes the game a lot more accessible (there is little to no system mastery involved), and because as the game doesn’t lock you into a combat minigame setup, players will likely do things other than thinking their only options are to attack or run away.

There is not even an initiative system of any sort! (There is an optional system to make sure everyone gets their turn.) The spotlight revolves around who it makes sense to next focus on, with the GM controlled adversaries getting their turn when players roll with Fear, or when the GM spends Fear to spotlight the adversaries.

For a game born out of modern D&D, this approach to combat is daring and surprising, to say the least. I will have to see how it works at the table – I have concerns about the lack of structure being difficult for many players versed in D&D.

Daggerheart has a weird relationship with character death. The game underlines multiple times how coming back to life is only possible with one spell, that may only be used once. At the same time, dying characters can just decide to live on multiple times. There is a cap, but with lucky rolling, they might never hit it. It reads to me as pretty much as forgiving as modern D&D. I do like that a dying character’s player gets to decide if they fight on, risk it all, or give up and go out in a blaze of glory.

Beyond the rules, the GM advice goes into detail on how to make sure combat is playing an important role in the narrative – and not just the bigger story being weaved at the table, also the player characters’ personal stories. There are guidelines for layering objectives, and how having multiple in a single combat allows you to build tension and force the heroes to make choices. For a fantasy game in the D&D vein, this is pretty advanced stuff, and something I find inspirational.

Adversaries remind me of D&D 4th edition monsters. You’re given a lot of advice on how to make them your own, but you’re looking at a fair amount of prep to customize these for your own needs. It’s not math heavy, as this is all art, not science, which sits at poor odds with the Battle Point system used to calculate which adversaries you should bring to a “fair” fight. It doesn’t read any better than D&D’s poorly balanced Challenge Ratings. The example adversaries given, however, are interesting, and the game goes to a lot of care in making all of them feel different, without making for unwieldy stat blocks – even high tier adversaries fit 2-3 on a single page! The downside is that the GM needs to internalize a whole lot of unique features the adversaries have, as none of it follows a clear pattern. There are more adversaries to choose from than I’d expect from a single book approach: it’s a generous offering!

Inspirational, not instructional

The GM is encouraged to improvise rules and mechanics for NPC, adversaries, environments, and scenarios. There is a decent amount of examples given, but this puts a lot of pressure on the GM, and gives little to no fallback in terms of “here’s a simple system you could use”. I don’t think this is very beginner friendly for the GM.

Same goes for how Fear can be used to adjust the pressure during a game. It’s a great approach, asking the GM to be proactive in managing tension during a session, but the book tells you come up with new rules on the spot, as needed. I do love the way it encourages making changes in a high tension scene. While the outcomes are not really codified in a way anyone might call “fair and balanced”, having a light system in place of just asking the GM to do all that on their own is a good approach. But again: this is advanced territory, and I worry how a fresh GM might fare with it without being intimidated.

The built-in GM agency puts a lot of weight on the GM. As an example of something that you would expect support in, there are no prices for any adventuring gear, including weapons and armor. Instead, the GM is instructed to give the players a choice of a couple of options, if they go looking for something to buy, and remove “a handful” or “a bag” of gold for it. I expect this will work mostly fine, but it’s supporting structure that I’ve come to expect and depend on, after decades of being conditioned on high fantasy adventure games.

While I like pretty much everything in the GM facing guidance, my issue is that it reads like a description of how the game’s designer runs their own games, without actually giving rules I could deploy at my table with a reasonable expectation of them working. There is no set of mechanics that build into a cohesive whole, probably looking broadly similar in one table to the next. This isn’t a flaw as such, but a GM should understand that they have to make the game their own.

As a detail that I like, the game encourages the use of D&D fourth edition style skill challenges. This is a mechanic I’ve varied in every single game I’ve run ever since I first run across it, so that’s appealing to me. But again: there are no hard rules on how to set this up. There are plenty of examples for you to figure out your own way.

I’m hesitant to even call this approach a tool kit, like some games which give you lots of options (like the 2024 D&D Dungeon Master’s Guide) – this is more like the Daggerheart designer talking with you, giving you material to think about, without giving you any solutions, or even blueprints. It is inspirational, not instructional.

Adventuring

There is a fun concept of putting together single shot adventures by filling in the blanks in a short narrative. This suffers from two things: there are as few options as the woefully lackluster 2024 D&D DMG tables, and none of this centers the story on the player characters. I have to call this a miss. Why not do a quick pass at character stories and relationships, and just pick one to highlight for the evening?

All those inspirational, not instructional rules come together at the very end: the campaign frames that close out the book are superb. They show how the game’s loose structure and rules can be shaped into very different fantasy gaming concepts.

All of this gets an in-depth treatise, and none of it is what you might call D&D flavor fighting fantasy á la Forgotten Realms:

- Horizon Zero Dawn (swapping magic for forgotten technology, complete with an intricate writing system, and a weapon upgrading and crafting system directly from the videogames)

- Dark Souls

- Shadow of the Colossus meets a western (with colossi fighting rules and western genre rules)

- Delicious in Dungeon (yes, with monster cooking rules)

- Game of Thrones

- Princess Mononoke meets Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind meets The Legend of Zelda

These are all very evocative, very different in tone and content, and all complete with heavily customized rules, dripping with flavor. Each one has an instigating incident pushing the player characters into the heart of the drama. It’s stellar stuff. I want to run all of these! They’re excellent, and I hope they will be expanded upon in later products.

Closing

Daggerheart is much bigger and much more ambitious than I expected, full of, indeed, heart, and challenging D&D players to try a different style of play – more collaborative, and character driven. I can’t wait to run it, even if some of the rough edges already feel like they’re in need of a second edition to smooth it down. I hope the game does good and we get to see what that might look like.

Leave a Reply